🐐 A photo tour of Winterthur and its odd Gentleman Farmer, Henry 🕵🏻

more mysteries of american history, gardens, & the unusual people who built them

Of the 7 gardens I visited in Delaware, Winterthur seemed most at war with itself.

What was it, exactly? A country farm on twenty four hundred acres of rolling hills? A giant 150-room mansion? A tribute to the history of American furniture? Pieces of the estate were breathtakingly open and simple — while the grotesquely enormous home sat patiently as the trees seemed to eat it alive.

I knew nothing of the du Ponts when we visited this garden in particular. I am struck by how you can admire an artist’s work in isolation, but as the expression of a human you know, it changes.

Even further, to know a family yet see the individual; to witness a person’s work and know the enormity of effort they exerted to push their own selves forward into their future — it reveals the capacity of a human life and reminds us that we have always been the same. That there have always been among us the ones who veer left when our world drags right.

Henry Francis du Pont

Henry Francis du Pont (b 1880) was the son of Henry Algernon du Pont and Mary Pauline Foster. By the time he was born, his mother had lost five children in infancy. Henry grew up with the only sister who had survived, Louise, in one of the largest duPont family estates. Louise was three years older than Henry, and after researching her work on her grandfather’s home (Eleutherian Mills), I imagine her to be as oldest sisters all are. But Henry struggled. He spoke quietly, was creative, collected birds eggs and stamps, and did poorly in school.

Henry’s father was a West Point graduate and Civil War hero — and known as a domestic tyrant. His children (and in the future, grandchildren) were only to address him in French. He did not allow anyone who’d been divorced to visit him. He ruled with an iron fist and sent his only male heir to Groton, a school meant for toughening boys up. Henry was 13. He graduated at the bottom of his class.

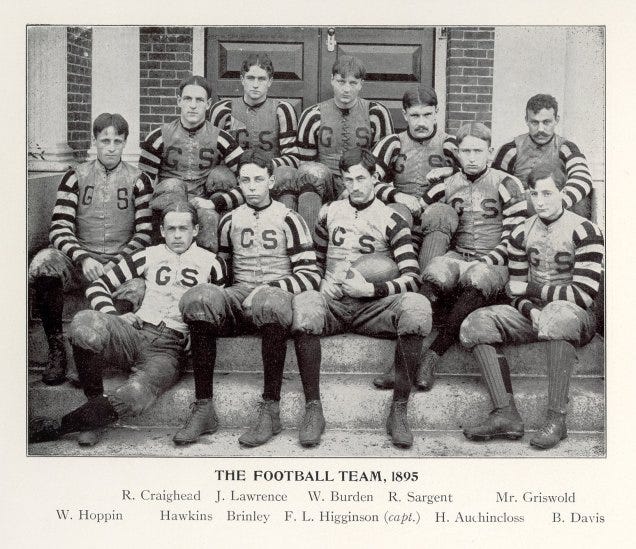

Sidebar: I don’t mean to write about Groton but I was curious. I found this photo, and I do want to smack the smirks off each of them (but hug poor Davis). I cannot help but to share that this research taught me about Endicott Peabody, a wealthy Episcopalian priest and boxer [his father a founder of JP Morgan Chase] whose goal was to recreate England’s Rugby School, prioritizing sports and moral virtues over education, to turn the nation’s wealthiest boys into men. It was touted as “the best” by Franklin Roosevelt, who sent all four of his sons there. The student W. Averell Harriman wrote of Peabody, “You know he would be an awful bully if he wasn’t such a terrible Christian.”

After a miserable time at Groton, Henry went to Harvard. In his junior year, he enrolled in Harvard’s Bussey Institution, whose mission was to educate “young men who intend to become practical farmers, gardeners, florists, or landscape gardeners,” as well as “men who will naturally be called upon to manage large estates.”

In 1901, at age 21, he wrote to his mother of his new found purpose: “sudden resolution … my great desire to really know something about flowers … In fact flowers etc. are the only real interests I have.” He added, “I do not think I am impulsive I hope not at least. I merely think it is the smouldering [sic] of latent thought which has burst into flame.”

Heartbreakingly, his mother died the next year. A life long collector of flowers, she never knew he received a D- in his first horticulture class, and also would never bear witness to his becoming one of the greatest horticulturalists in America. Later in life, Henry told his daughter Ruth that when his mother died, he decided to “give up feeling.”

I will share this gem of an excerpt from Walter Karp:

Henry accomplished virtually nothing for an entire decade after he was graduated from Harvard in 1903. The prime of his young manhood is an almost perfect blank. He lived with his father at Winterthur, bought a rare tree, planted a few bulbs.

Not until he was thirty-four did Henry F. du Pont do anything on his own initiative. In 1914 he bought seventeen Kurume azaleas—then rarities fresh from Japan— with the happy notion of one day planting them in the woods overlooking his father’s house, which the colonel had recently turned into a French Renaissance château. By then it was abundantly clear to the colonel that his only son had no future in the world beyond Winterthur. Since he loved planting trees and flowers, the colonel put him in charge of Winterthur’s farm. Henry found the assignment agreeable, for he had no interest in business or politics or society and very little wish to leave Winterthur at all. It was his haven in a world that had little, if any, use for him.

The two hundred year war between nature and gunpowder in this family fascinates me. The patriarch of the du Ponts (Éleuthère Irénée du Pont) was a trained botanist and horticulturalist in France before fleeing to America during the French Revolution and creating the American gunpowder empire. In a family where a great love for horticulture prevails through each generation, it is a wonder to me that it is also rife with fathers tormenting their sons who inherited one love without the other.

It is also no wonder to me that Henry waited until after his father’s death in 1926 to come to terms with his passions. His sister recounted, “Father would take Harry and me by the hand and walk through the gardens with us, and if we couldn’t identify the flowers and plants by their botanical names, we were sent to bed without our suppers.” He must have hated his true love first.

After his mother’s death, Henry traveled Europe to see all of the great gardens with a new friend: Marian Coffin, one of the first and only female landscape architects of the time. Harvard did not admit women and she was one of two women enrolled in MIT’s landscape architecture program - in a 500 student body. They became life long friends. No one would hire women as landscape architects, but Henry employed her for decades at Winterthur - even through the Great Depression. They would write letters back and forth over the course of their life, asking one another’s opinions on their ideas.

Henry did marry. After seeing a very extroverted New York socialite named Ruth Wales for seven years, they wed in 1915, and went on to have two daughters. They lived in their family home with Henry’s father for the first eleven years of their marriage until he died. Ruth despised him, and became anxiety ridden by the experience, ultimately taking “nerve medicine.” Understandably, she did not like Winterthur, and referred to the estate as "Frog Hollow." She spent most of each year instead at their Park Avenue apartment or their summer residence at Southampton, living her life freely as an aspiring composer and enjoying city life.

Ruth and Henry’s marriage appeared affectionate despite their independence and separate lives (though we might should start saying ‘because of’). Henry was an involved father and visited his family often when they traveled. His daughter Ruth wrote, “He took over many tasks that were normally the province of wives and mothers: home furnishing, meal planning, and the supervision of what my sister and I wore, even to our party shoes.”

I realize I have written far more about Henry than the garden itself, but my hope is that you get the privilege to visit Winterthur at some point in your life, and you get to see it with truer eyes than I did.

Admittedly, I took the least photos of this garden as the sun was high and we were tired, but I will never forget the views of the farmland from the edge of Sycamore Hill, the walls of lilac, and the emerald forest of pachysandra and solitary, upright ferns.

To see more of the garden, there is a 10 minute vignette on The Garden Chronicles, and I’ve added photos below taken by a friend of Henry’s from the 1920s. I immediately note that the original plantings are exceptionally feminine, bloomy, and showy than the green estates are today. Here as well are some facts about the garden that I loved:

Henry planted 70,000 bulbs in the first two years of inheriting Winterthur

He hired 90 gardeners to maintain the 200 acre garden and beyond

Henry dedicated his life to the naturalist style, aspiring to create gardens that felt ‘they’d always been here.’

Winterthur is so large that there are 99 homes on-site which housed 250 members of staff

Winterthur has it’s own railroad to welcome in guests as well as it’s own post office

His signature color combination in the garden was mauve against chartreuse

Henry kept detailed notes on which china was used for each guest so that if they ever returned, they would be served on china they had not seen before

Henry spent the rest of his life building Winterthur, propagating unusual plants, breeding cattle, hosting parties, and assembling the largest collection of American furniture in the country. He refused to refer to himself as anything but a farmer, and sometimes a gentleman farmer. An odd man until the end, he is one of my favorites.

Until the next garden,

Lauren

“Sell your cleverness and buy bewilderment.” Jalal ud-Din Rumi

REFERENCES

https://www.americanheritage.com/henry-francis-du-pont-and-invention-winterthur

https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/first/l/lord-dupont.html

https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2003/07/henry-francis-du-pont.html

Stunning - this was beautiful to read!